Core 101: What It Is and Why It Is Important

Can you name all the structures that make up “the core”?

Many people do not realize just how extensive the anatomy and physiology of your core truly is and how many structures in the body contribute to it. Gaining a thorough understanding of your core and how it works may be the missing piece of information you need to gain a fully functional core and decrease your risk of back injuries.

What the heck is the core?!

I should really start off by addressing the elephant in the room, so here it goes... Technically, there is no simple definition of the core (anatomically speaking).

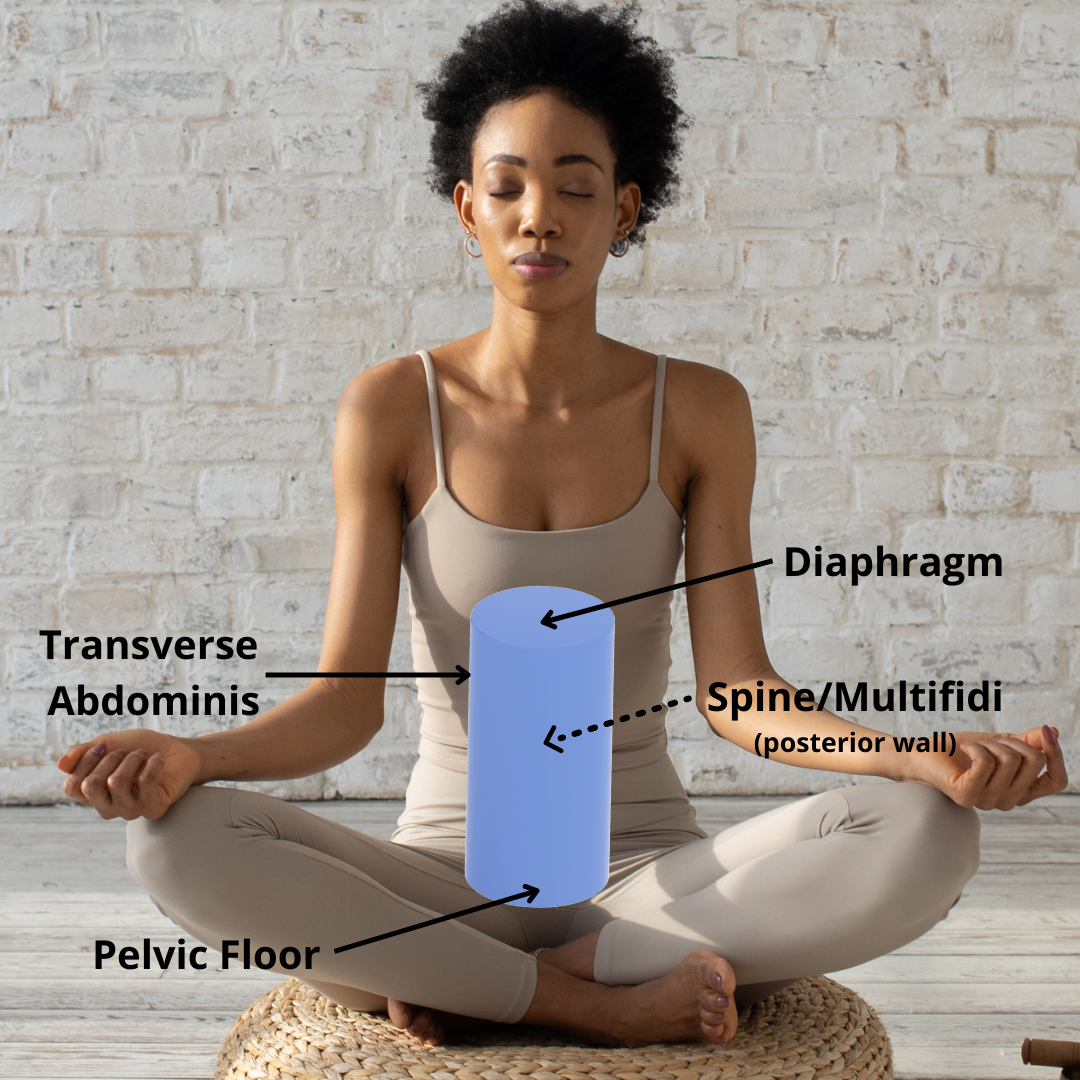

It seems to have become commonplace to believe that the epitome of all core strength = 6-pack abs. In reality, however, the core is much more comprehensive than the 6-pack muscle (the rectus abdominis). It consists of multiple structures that create a 3-dimensional cylinder, if you will, around your abdomen that serves as a strong foundation from which all movement stems.

While there are arguments to be made about which muscles are the “true” core muscles, just like there are arguments about whether Pluto is really a planet, for the sake of this article we’ll focus on the basic core musculature (we still love you, Pluto).

If we define the core by its main function (providing stability) then the muscles that contribute to its function would be considered core muscles.

Imagine your abdomen is a cylinder made from the following parts:

Top = Diaphragm

Front/Sides = Transverse Abdominis

Back = Spine + Multifidi

Bottom = Pelvic floor

Some researchers and practitioners even include the glute, psoas, pectoral, and latissimus dorsi muscles (among others) in defining the core because of the significant roles they play in helping to stabilize the spine. We are not going to get into how these structures contribute within this blog, but will absolutely detail their importance in future blogs.

Let’s dive into each of the structures listed above, shall we?

The diaphragm. The diaphragm is a dome shaped muscle that sits toward the bottom of your entire rib cage, 360 degrees around. During normal breathing its contraction helps to pull air in (inhale) and its relaxation helps to push air out (exhale) of the lungs through a negative pressure system. This is considered the diaphragm's primary function.

A secondary function of the diaphragm contributes to an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. When the diaphragm contracts, it creates a downward force on top of the abdominal cavity, thus creating the top of the cylinder.

The Transverse Abdominis. While the abdominal wall actually consists of multiple layers of muscles and connective tissue, the transverse abdominis muscle gets most of the credit here because it is the deepest of the anterolateral (front/side) abdominal muscles. It is often referred to as the “corset muscle” because of the tension it creates in a similar fashion as a corset around the abdomen. This tension acts on intra-abdominal pressure as well, increasing pressure with its contraction.

The Spine and the Multifidi. The spine obviously makes up a portion of the back of the cylinder, as it is what we often imagine when we think of our backs. The multifidus (multifidi in its plural form) is a muscle that spans multiple vertebrae on the spine and is a major spine stabilizing muscle. We each have multiple multifidus muscles running down the length of our spines, thus the back of the cylinder.

The Pelvic Floor. The pelvic floor creates the bottom of the cylinder and is made up of multiple muscles that run between the tailbone and pubic bone. These muscles support your pelvic organs and control functions like the flow of urine, for example. The activation of these muscles also contribute to intra-abdominal pressure balance.

Why is having a strong core so important?

So what’s the big deal here? Why should you be aware of all these individual structures that make up the core?

Well, to be quite frank, you cannot perform any movement without first activating your core musculature. Research has shown that the muscles that make up the core will activate milliseconds before your superficial and primary mover muscles. This means that your core is firing with movements as simple as picking up your coffee cup.

Here is how it works (simplified, of course): the proper co-contraction of the muscles listed above produces stiffness that acts as a protective and stabilizing force for your lumbar spine. Hence the 3-dimensional cylinder.

The stiffness generated creates and controls intra-abdominal pressure that allows the spine to resist excessive movement and moments of instability.

If we lack the ability and/or coordination to stiffen our core, our spines become susceptible to injury when put under any type of load, even what you might consider to be light. For example, wearing a backpack or purse, turning your head to check your blind spot, or bending forward to pick something up.

These movements, though subtle, can transfer enough of a shearing, rotating, or bending force that could result in you “throwing your back out” if you cannot prevent an excessive amount of movement within the joints. Now imagine the the same movements but under an increased load… yikes! A lack of core strength under heavy loads could result in more considerable injuries such as a herniated disc or SI joint sprain, to name a couple.

Unfortunately, the overwhelming majority of back injuries that we see in our chiropractic clinic are a result of repetitive stress injuries from everyday movements. Think about the number of times you look down at your phone or bend forward to put your shoes on throughout the day. Those movement patterns count! To learn more about how your everyday movement might be increasing your risk of injury, check out our blog Changing the Way You Think About Movement.

Ohh, now I get it!

So there you have it. The core, in its most basic form, is made of a series of muscles and connective tissue that create and maintain pressure in the abdominal cavity to aid in stabilization of the spine and form a solid base from which your body can move efficiently while preventing injury.

Next time you are “doing some core” think about the cylinder and how it needs to be strong from every angle in order to prevent injury. Keep an eye out for next week’s blog post all about understanding core stability!

If you have any questions or think that you might be experiencing pain due to a lack of core stability, call to schedule a free 15 minute consultation with one of the Momenta Doctors to discuss your concerns and figure out the best plan of action for you.

Follow our booking link here to schedule your free consultation online now!